By Pawan Sinha | President and Project Leader

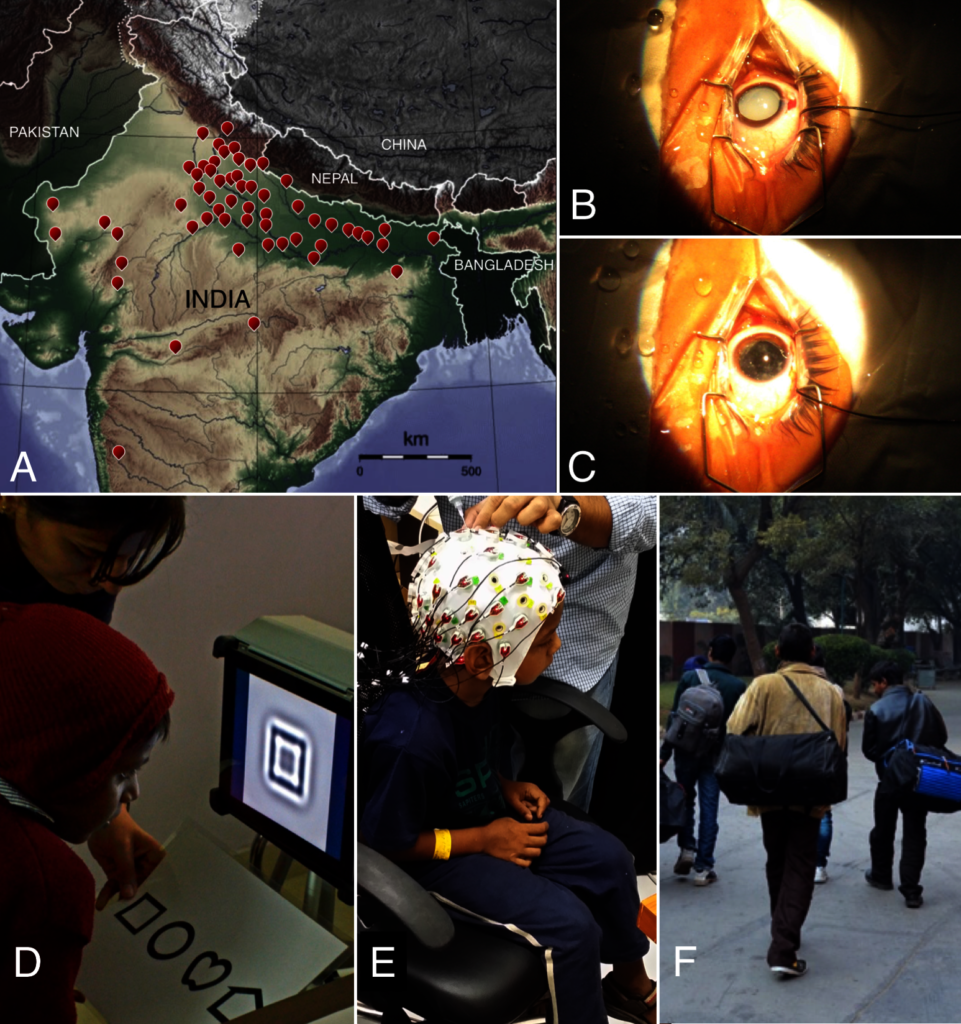

Image caption:

A: Locations of Prakash pediatric ophthalmic screening camps conducted so far. B & C: A child’s eye, before and after removal of a congenital cataract. D & E: Scientific studies to characterize visual development following late sight onset. F: The human benefit: four individuals who were born blind and were treated by Project Prakash have gained visual function and independence.

-------------------------

For most scientific enterprises, societal benefits are realized long after the research effort. However, in rare instances, even the process of conducting research directly benefits people’s lives. We have been fortunate that in Project Prakash we have been able to identify and operationalize one such instance. The overarching mission of Project Prakash is to bring light into the lives of curably blind children and, in so doing, illuminate some fundamental scientific questions about how the brain develops and learns to see. Hence, the Project represents a confluence of humanitarian service and basic science.

India is home to one of the world’s largest populations of blind children. It is estimated that nearly 400,000 children in the country are either blind or severely visually impaired. The visual handicap, coupled with extreme poverty greatly compromises the children’s quality of life; childhood mortality rates are greatly elevated and prospects for education are severely diminished. Project Prakash seeks to identify and treat blind children, and simultaneously, build awareness amidst the rural populace regarding treatable and preventable blindness.

Embedded in the humanitarian aspect of Project Prakash is an unprecedented opportunity to study one of the deepest scientific questions: How does the brain learn to extract meaning from sensory information? The humanitarian initiatives of Project Prakash are creating a remarkable population of children across a wide age-range who are just setting out on the enterprise of learning how to see. The Prakash researchers have been following the development of visual skills in these unique children to gain insights into fundamental questions regarding object learning and brain plasticity. This is a unique and unprecedented window into some of the most fundamental mysteries of how the brain learns to extract meaning from the world.

Over the past year, with support from several individual donors and organizations, Project Prakash has conducted extensive rural outreach, which involves providing pediatric ophthalmic screening in remote regions of India with limited medical access. In 2-3 screening camps per month, teams of optometrists, ophthalmologists, social counselors and field health workers have evaluated children on multiple dimensions of eye health. The majority need and receive outpatient care (refractive correction, eye drops for infections). Those with congenital blindness are brought to New Delhi, where they undergo thorough ophthalmic examination to assess if their blindness is treatable. Following consent, each child is provided free high-quality surgical treatment, and stays at the hospital for several days to ensure good clinical care during recovery. After discharge, children are asked to return for follow-up assessments. Contingent on parent/child consent, the children participate in scientific studies during each hospital stay (medical treatment is never contingent on agreement to participate). So far, we have screened ~43,000 children, provided surgeries to over 460, and non-surgical care to over 1400. Our studies have yielded a rich body of literature regarding several aspects of post-operative visual development.

One of the most far-reaching results from Project Prakash is evidence of recovery even after prolonged congenital blindness. These findings argue for a reconsideration of some long held conceptions regarding brain plasticity and time-lines of learning. Having followed the post-operative development of several children, my students and I have found that while some aspects of vision, such as acuity, are compromised by a history of deprivation, there is evidence of skill acquisition on a variety of functional vision tasks ranging from simple shape matching to object and face recognition. The human brain, these findings suggest, retains an ability to launch programs of visual learning well after the normal period of their deployment has passed. These results have significance for basic neuroscience as well as the practice of pediatric ophthalmology and the implementation of late stage blindness treatment programs.

Over the course of this work, Project Prakash has revealed several sociological issues that came as surprises to us. For instance, we would never have expected that parents might actually prefer to have their child remain blind just so that they can stay enrolled in a school for the blind where they are provided with food and clothes. Yet, the level of poverty in some households is so extreme that this happens. Another surprise for us has been the difficulty Prakash children have encountered in entering the educational mainstream despite having sight. But, their age (too old to be enrolled in grade 1) often keeps them from starting their educational journey. This is indeed a tragedy and one that we have started working towards addressing. We have just commenced an educational program to complement the medical and scientific missions of Project Prakash. This program will provide a ‘compressed’ educational course to the Prakash children to bring them up to an age-appropriate level so that they can then enter the regular educational stream. In addition, we shall impart vocational skills to the children with an eye towards facilitating their journey to eventual financial independence.

Project Prakash continues to be a remarkably fulfilling enterprise for all of us on the team. It is hard to describe the happiness surrounding the transition of a blind child to the world of sight. We hope that in the years to come, we shall be able to bring the gift of sight to all children languishing with treatable blindness. And, in bringing light into their lives, we are sure to bring light into our own.

By Pawan Sinha | Founder

By Sheila B. Lalwani | Executive Director

Project reports on GlobalGiving are posted directly to globalgiving.org by Project Leaders as they are completed, generally every 3-4 months. To protect the integrity of these documents, GlobalGiving does not alter them; therefore you may find some language or formatting issues.

If you donate to this project or have donated to this project, you can receive an email when this project posts a report. You can also subscribe for reports without donating.